Being a very rural area, Heilwood wasn’t linked to any surrounding towns via paved roads until the late 1920s. Three separate paving projects are documented.

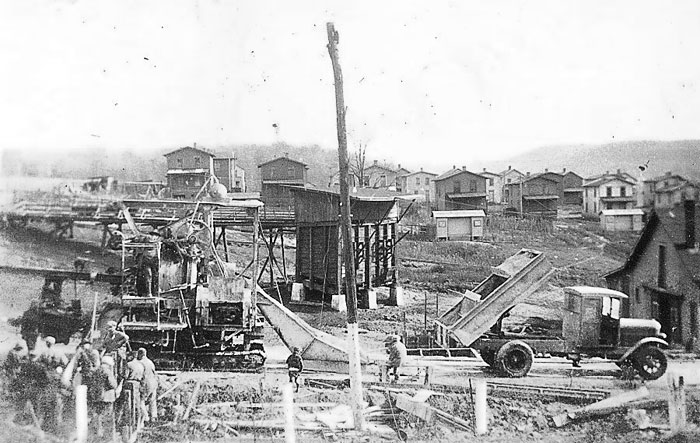

The first project was for a section of roadway approximately three miles long, extending from the railroad crossing south of Heilwood to near the Griesemore-Pineton intersection north of Mentcle. Russel Brothers of Youngstown, Ohio was awarded the contract and began the preliminary grading work on the 16,000 foot project on July 19, 1928. With 100 days allowed to complete the project, Russel Brothers actually worked 142 ½ days. The roadway was opened to traffic on August 12, 1929, with the final inspection of the project on September 19, 1929 (see photos).

The second and third paving projects not only constructed the ‘Y’ north of Heilwood but paved the entire roadway into Penn Run. The Blue Ridge Construction Company of Uniontown, Pennsylvania was the contractor for both projects. Begun on April 29, 1930, the approximately six-mile stretch of roadway was completed on August 30, 1930, with the final inspection taking place October 30, 1930. The time allowed for the projects was 105 days and it was completed in 103 working days.

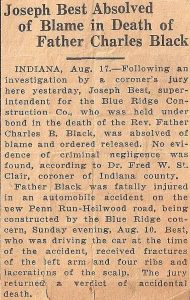

It was on this newly paved road that Father Charles Black, the Catholic Priest in Heilwood, was fatally injured while riding with Joseph Best, the Superintendent of the Blue Ridge Construction Company, on August 10, 1930. While rounding a curve on the new roadway, the car reportedly left the road surface and overturned, throwing both individuals from the vehicle. Best and Father Black were both taken to the Heilwood Hospital, where Father Black was pronounced dead shortly after arriving by the attending physician, Dr. George Lyons. Best, while suffering a broken arm, fractured ribs, and lacerations of the scalp, survived. It was later reported that “shoulder work” had not been completed on the roadway and that this may have contributed to the accident.

On August 16, 1930, a coroner’s jury meeting held in Indiana, Pennsylvania investigated the accident and absolved Best of any wrongdoing, finding there was no evidence to suggest that he was driving recklessly or under the influence of alcohol (see photo).

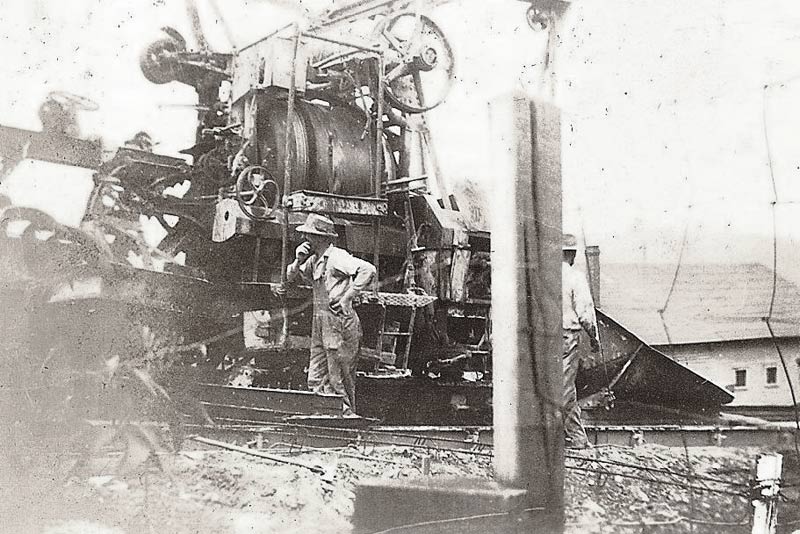

The bottom two photos show how the roadway was made, and detailed descriptions of these machines were provided by the Historical Construction Equipment Association of Bowling Green, Ohio:

The first photo shows a form-riding concrete finisher. The sides of the slab are shaped by steel forms; you can see one form on the side facing the camera, along with the pins that are driven into the ground to hold them in place. The finisher travels on top of the form in a way similar to a railraod car on steel rails, except the flanges that keep it on the forms are on the outside instead of the inside of the wheels. The finisher puts the final surface on the slab; a spreader moving ahead of it strikes off piles of concrete placed on the roadbed by the paver. After the conrete had set, the forms were removed.

This technology has been obsolete since the early 1960s; since that time, concrete pavement is laid mostly by slipforming, a technology by which the spreading and finishing functions are combined in one machine that travels on the ground and pulls the form along with it, and by which the concrete is of a stiffer composition than before so that it does not require forms to contain it as it sets.

The next photo shows the kind of paver mentioned above. Pre-proportioned batches of aggregates and cement were dumped by trucks into the skip at right. The skip was raised to discharge the dry materials into the mxiing drum, which is directly above and behind the man in the photo. After the concrete was mixed, it was discharged out the opposite end into a bucket that traveled on a swinging boom. The bucket and the base of the boom are visible in the photo; the man appears to be studying it. The operator directed the bucket to where the concrete was to be dumped, and opened the bucket by pulling on a rope. The bottom of the bucket opened, the concrete fell out, and the operator returned the bucket along the boom to receive another batch of concrete, which if all went well on the larger pavers would be ready to discharge into it. The dry batch paver was invented in 1919, and remained in use until the early 1960s as well; it was replaced by central mix batch plants that mix the conrete away from the worksite; trucks deliver the mixed concrete to the site.

HEILWOOD TO NOLO (1937-1940)

Although not a paved road project, a contract was awarded to A. A. White, Inc., of Lebanon, Pennsylvania on May 23, 1938 that would nearly link Route 54 just south of Heilwood to Route 301 (Route 422 today) near the crest of the Nolo Hill. The contract was for a 3.03 mile stretch (just short of connecting with Route 54), at 14 feet wide with a traffic-bound surface. This meant that the road, previously just a dirt road, would be constructed of multiple courses of coarse aggregate over a prepared sub-grade. In other words, a gravel-covered road.

Work was begun on April 19, 1938 and completed on August 26. Forty-five days were allowed for the work and 45 days were utilized for its completion. All the aggregate for the contract was purchased from local sources near the work site.

In 1940, utilizing similar materials as in the previous contract, the remaining roadway from Route 301 to Route 54 south of Heilwood was completed.