Following World War I, the demand for coal declined markedly. The many owners and operators who had expanded their coal mines and added employees during the war were now forced to drastically reduce their overall production. As a result, they also began campaigning to slash the wages of the miners they employed.

At the February 1922 United Mine Workers meetings in Indianapolis, the delegates stood firm against any wage concessions, and in fact demanded a five-day work week along with a six-hour day. It soon became obvious that the coal operators, who had already refused to take part in a four-state wage conference, were not going to accept the demands of the union. On April 1, the miners honored the birthday of former UMW leader Johnny Mitchell with parades and speeches. That evening, newspapers ran the headlines that the UMW had declared a national coal mining strike.

The coal operations in and around Heilwood once again came under intense UMW pressure, not only to have the miners leave their workplaces in support of the strike, but to also have them organize as members of the UMW. Up until this point, the coal companies around Heilwood had used regular policeman, additional sheriff’s deputies, or the state police to prevent any union representatives from coming into the community and successfully organizing the miners at any of the seven operating mines.

On July 13, a hurried call went out to the sheriff’s department in Indiana, concerning a possible march by striking miners that had gathered at Colver with the intention of going into Heilwood. The march never materialized, but other, more serious events followed. On July 18, the miners in both the #9 (Brownstown) and #11 (Mentcle) mines left their workplaces in support of the UMW. This action by the miners and the UMW caught company officials by surprise.

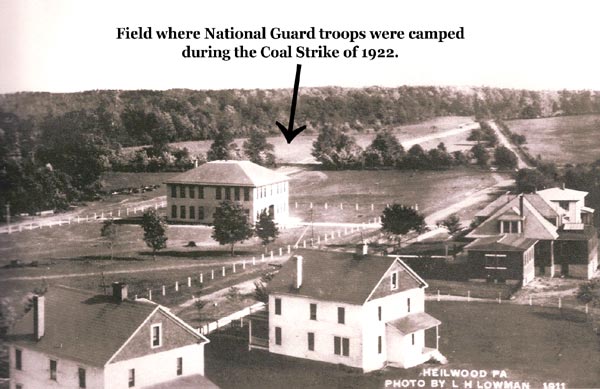

Officials in Heilwood, sensing a possible attack on their mines, drafted a letter to Pennsylvania Governor William Sproul on July 20, requesting the deployment of National Guard Troops to assist in the continued production of coal. Their letter pointed out that Heilwood was almost the geographical center of a great many coal mining towns, and that there were facilities in the town that could accommodate the troops and their equipment. In addition, the officials noted that they felt the Heilwood miners would continue to work if they did not feel intimidated or threatened. Whether this letter influenced Governor Sproul is unknown, but within a week of it being sent, a cavalry troop and machine gun detachment were sent to Heilwood (Troop C, 104th Cavalry of Harrisburg).

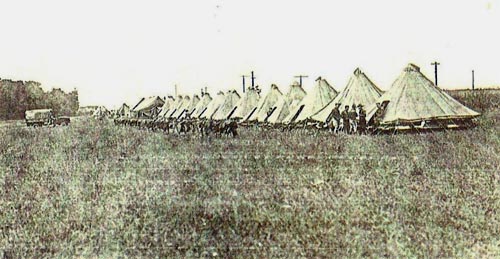

The troop reportedly numbered over 240 men*, and their arrival was a total surprise not only to the community, but also to the UMW. This deployment of National Guard troops was the first since the 1902 deployment in the anthracite coal fields of eastern Pennsylvania.

The troops were stationed a short distance northeast of Heilwood, along the main road into town (Route 54) (see photos). This land had once belonged to the Heilwood Dairy Company, which had ceased operation several years earlier.

Referred to as the “Boys in Khaki” in the area newspapers, the National Guard troops patroled the local roads from 6 a.m. every morning until the miners left the pits, protected company property, and prevented any mass meetings of workers within the community. Although detailed information concerning their stay in Heilwood went mostly unreported in the newspapers, there was a mention that the local Presbyterian Church reserved a section of pews for any of the troops that wanted to attend services.

On July 22, John Brophy, President of District #2 of the UMW, appealed to Governor Sproul to reverse his actions that prevented mass meetings by the miners, but to no avail. A week later, Judge Langham (Indiana, Pa.) issued a preliminary injunction against District #2 of the UMW, which restrained striking miners and union officials from interfering with the operation of the Bethlehem Mines Corporation mines in the Heilwood area, and prevented them from undertaking any activity that hindered the miners from going to work. This preliminary injunction became permanent in September 1922 and remained in effect until 1928.

Although production was halted at the #9 (Brownstown) and #11 (Mentcle) mines for a short time by the UMW organizers, the presence of the troops and Judge Langham’s injunction soon enabled normal production to resume. The other five mines closest to Heilwood were not affected by the stoppages and continued to produce coal throughout this time.

Near the end of August, a settlement was reached with many (though not all) of the coal operators in District #2, and a contract was signed. Many newly unionized mines in the Somerset area of District #2 were not included in the contract, and they continued the strike until August 1923 to no avail.

The September 6, 1922 issue of The Indiana Evening Gazette reported that the National Guard troops stationed in Heilwood for the previous six weeks had departed, and that their duties would be taken over by State Police personnel.

Almost a decade after the Strike of 1922, the Heilwood area mines were finally organized, and became a part of the UMW. Many years after the National Guard troops had left Heilwood, their encampment area on the edge of town was always referred to as “Soldier’s Field” by the residents.

*Actual photographs of the encampment put the total number at approximately 70 men. This discrepancy may be due to some of the troops being dispatched to other locations after arriving in Heilwood.